If the committee of 47 scholars assigned the task of translating the Bible into English for King James I had followed undeviatingly the practice of exegesis rather than eisegesis, we would not have wound up with a few rare but erroneously worded and punctuated texts. But lest we be accused of coming down too hard on these scholars, we need only recall that their knowledge of the original Greek language in those Renaissance times surely far surpassed that of today’s best scholars.

We should also bear in mind that the committee’s access to the best extant Biblical manuscripts was extremely limited. Still, these true Renaissance men endeavored to stay as close to the original wording as humanly possible. Their achievement, and the high esteem with which their literary accomplishments continue to be held, bear mute but powerful testimony to an enduring theological and literary contribution.

Perhaps the most striking example of a rare human lapse is their interpretation of Luke 23:43b. The distinction between the two technical terms mentioned at the outset will become clear as we take a closer look at this familiar text of Scripture and compare it with a few contemporary examples of misinterpretation.

New Testament Greek

Keep in mind that New Testament Greek originally possessed no lowercase letters, no punctuation, and no spatial separation between words. Pretending for the moment that Elizabethan-era “King James” English is equivalent to Koine (commonly spoken) Greek, we render the Luke 23:43b word string thus:

VERILYISAYUNTOTHEETODAYTHOUSHALTBEWITHMEINPARADISE

Those Authorized (King James Version, 1611) Bible translators interpreted this text by reading into it their own preconceived ideas (Webster’s definition of eisegesis). Though assiduously true to the original Scripture manuscripts an amazingly high percentage of the time, this rare but confusion-fraught instance reveals how on one occasion they mistakenly punctuated Jesus’ famous promise to the dying but repentant thief on the neighboring cross:

“Verily I say unto thee, Today thou shalt be with Me in Paradise.”

We say these

scholars must have read into the text their own ideas because they truly believed that at death, one’s “soul” is

transported immediately either to Heaven or Hell. This error was not confined to their day merely, but sadly has

been popularized by the vast majority

of Bible expositors ever since. So-called dynamic translations of the Bible, however helpful they may be in making

difficult passages understandable to the modern reader, cannot be depended upon to assist the Bible student

with textual analyses faithful to the original

manuscripts.

No, the mistake that the KJV committee made with respect to their translation of Luke’s text lay rather in their failure to apply the vital principle of exegesis when interpreting this passage of Scripture. Had they more consistently followed their usual exegetical practice, leaving private interpretation out of the question, the same passage would have taken on a most significant — and correct — rendering of punctuation:

“Verily I say unto thee today, Thou shalt be with Me in Paradise.”1

According to the aforementioned book of Noah (Noah Webster, that is), exegesis is the explanation or critical interpretation of a text. It is entirely objective and therefore does not impose unwarranted personal preconceptions. A proper understanding of this distinction will serve the modern Bible scholar in very good stead, be that scholar a trained theologian or a layperson.

Two Present-Day Examples

To illustrate our point with examples taken from life in the present-day world, let us briefly reproduce two expressions in turn.2 We shall render them first, as before, without small letters, word spaces, or punctuation.

ISAWTHEPERSONWITHMYTELESCOPE

Well, now, does this mean that I saw an individual by means of the magnifying powers of my own telescope? Or could it mean that I spotted someone — perhaps even a thief — in possession of my tubular optical instrument? Context, you see, makes all the difference.

Let us conclude with one more example. It illustrates how ambiguity can lead to humorous, albeit unintended results.

NOTHINGISBETTERTHANYOURCOOKING

What do you make of this expression? Does it seek to praise a culinary expert, or is it instead a veiled sarcasm bemoaning an inept cook’s unpalatable meal? In other words, does this expression say, “Nothing is better than your cooking”? Or does the opposite apply: “Nothing is better than your cooking”? The strategic placement of printed italics or of vocalized inflection can make all the semantic difference. In the first instance, one might reword the expression to say, “Your cooking is unsurpassed!” In the second, things might come out rather differently: “Going without food would be preferable to such lousy cooking as yours!”

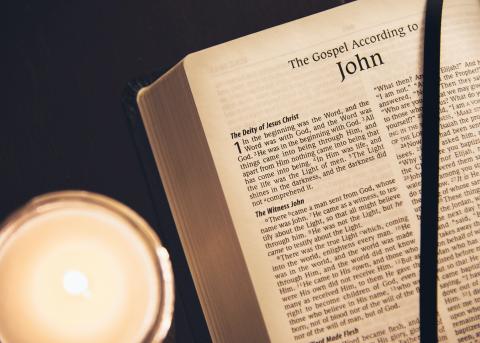

The knowledge of surrounding contexts is also very helpful. That is part of good, systematic exegesis. In the case of our original Scripture passage in Doctor Luke’s Gospel, it becomes obvious that Jesus did not intend for the thief to understand that Paradise was assured that same day, for in John 20:17 (var.), He admonishes Mary Magdalene: “Touch Me not; for I have not yet ascended to My Father.” Taking cognizance of the entire surrounding context, in this instance by comparing another Gospel account, makes it perfectly clear that Christ Himself had not yet returned to Paradise. A temporary ascension to Heaven soon must have taken place, for eight days later doubting Thomas insists on touching His Lord (John 20:26–29). Moreover, Christ’s permanent ascension to Heaven lay 40 days in the future (see Acts 1:3–11).

In similar cases involving events in Christ’s earthly mission, familiarity with the context of all key post-crucifixion events, as recorded by all four Gospel evangelists, can be a very important aid to the Bible student’s accurate understanding of any single text in isolation. As always, the whole Bible is its own best expositor.

Call to Action

Any student of Scripture does well to make the most intelligent use of all the reliable research methods available; in fact, these methods are indispensable. Among these, open-minded investigation of immediate, surrounding, and overarching contexts,3 along with a readiness to allow Scripture to interpret itself, have the power to transform a mere eisegete into a bona fide exegete.

Will you ask the Holy Spirit to guide you and empower you to know and share accurately the beautiful message of God’s Holy Word in all its richness?

- The apparent reversal of the words “shalt” and “thou” in the original KJV is not what we mean by eisegesis, as the Greek expression for “shalt be” comprises just one word, while the word “thou” is entirely lacking because the Greek verb tense indicates the person addressed. Though not necessarily endorsing it globally, Lamsa’s is the only translation of the New Testament known to this writer that does not misplace that infamous comma: “Truly I say to you today, You will be with Me in Paradise.” George M. Lamsa, The New Testament According to the Eastern Text (Philadelphia: A. J. Holman Company, 1940).

- Both examples adapted from a joint essay by Stanford University’s Thomas Wasow, Amy Perfors, and David Beaver, “The Puzzle of Ambiguity,” which may be read in full on this Web site: http://64.233.161.104/search?q=cache:O82R30o0ZOYJ:www.stanford.edu/~wasow/Lapointe.pdf+%22ambiguous+expressions%22+%22examples%22&hl=en&client=firefox-a.

- An excellent resource on this topic is Lee J. Gugliotto, Handbook for Bible Study: A Guide to Understanding, Teaching, and Preaching the Word of God (Hagerstown, Md.: Review and Herald Publishing Association, 1995), especially the introduction and chapter 1. Special thanks also go to Edwin de Kock, of Edinburg, Texas, whose thorough knowledge of languages and history produced several incisive and valuable suggestions.