One man’s willingness to die for truth laid the foundation for a worldwide movement of freedom.

John Huss’s eyes drifted from the paper in his hand to the quiet landscape of Hussinetz, Bohemia, that autumn day in 1414. His mind thought back to the bustling capital city of Prague, where stood his own dear Bethlehem Chapel. There, every week, he had boldly preached God’s Word to hungry souls in their own familiar language and fearlessly rebuked the shameful crimes of the papacy.

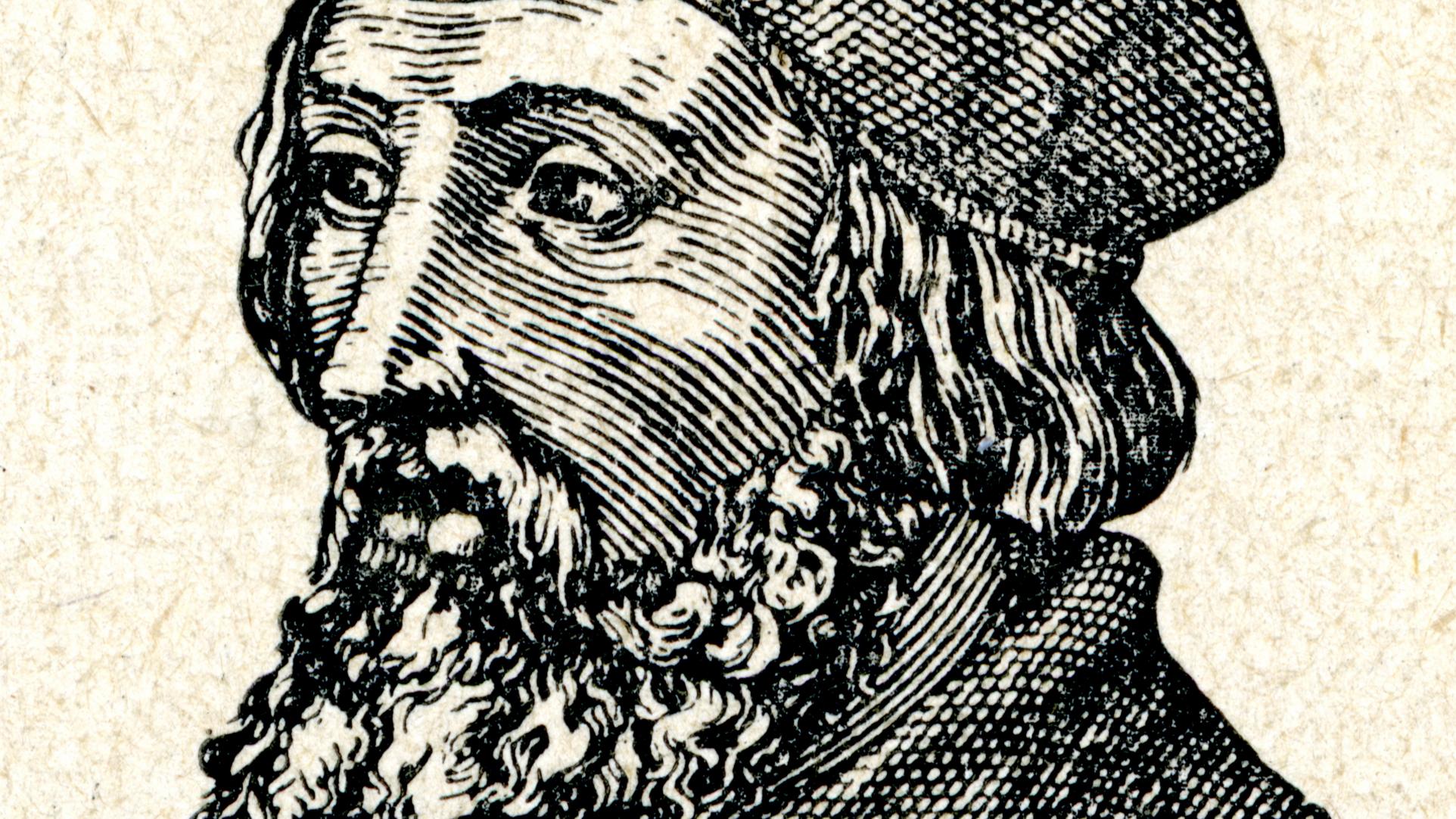

Born July 6, 1373, Huss attended the University of Prague. He became deeply interested in the English Reformer John Wycliffe, whose writings had found their way into Bohemia. From his pulpit at Bethlehem, Huss taught that the Scriptures, not traditions and rituals, were the ultimate pattern for the Christian. Idols and relics, he said, were useless.

One hundred years before the Protestant Reformation, John Huss preached Bible truth in the familiar language of his Czech people.

Alarmed by Huss’s forthright and powerful influence, the Roman Church twice pronounced an interdict on the Bohemian capital, depriving its people of all religious benefits. Both times Huss retired to Hussinetz, his country home, where he spent time fortifying his understanding of Scripture. Long-buried truths, such as salvation through Christ alone and Christ as the true head of the church, unfolded more clearly to his view.

Foreboding

That morning in Hussinetz, Huss looked again at the paper in his hand—the summons to a church council in Konstanz, Germany. He well knew that such a trip at this time might result in his death. There was the official safe conduct, granted by Emperor Sigismund of the Holy Roman Empire, but its certainty was doubtful.

Nevertheless, Huss and his party turned their faces toward Germany. Crossing the Bohemian border, Huss expected never to return.

He reached the lakeside city of Konstanz on November 3, 1414. In accordance with his safe conduct, he was housed in a small townhouse on one of Konstanz’s quaint, cobblestone streets in the shadow of the city tower.

However, his freedom was not to last. Within a month, Huss was imprisoned in a Dominican monastery on the water’s edge. Its imposing white walls did not reveal the filthy inner cell where Huss was cast. Contracting a violent illness, he came very close to death.

Huss was next imprisoned in Gottlieben, a small, sleepy town across the Swiss border. Behind the cold, gray, turreted walls of the castle, Huss could gaze down on the wide, blue Rhine, across which lay the city of Konstanz. This city had suddenly risen to significance in religious affairs as more than a thousand churchmen, not counting civil dignitaries, had assembled for this high church council with the one main purpose of ridding the church of heretics, namely John Huss.

Trials and Mockery

Huss’s trial took place months later on June 5, 1415. Hundreds of eminent clergy and princes gathered inside the massive, dark-timbered council hall. Standing out from the assembly was Emperor Sigismund himself—tall, eloquent, and dignified, yet secretly cowering at the combined splendor of the great men of Europe before him. Huss was shown his own writings and then was requested to recant these teachings. He calmly attempted to explain that he could not recant unless shown to be in error, but the enraged bishops and cardinals began to shout and scream, deliberately drowning out the Reformer’s voice.

Attempts to continue the trial were useless, so it ended in great confusion. After the second trial, an anxious Sigismund, wishing to convince Huss to recant and end the miserable process, sent him a contract of surrender. But the paper came back unsigned. By a small, dishonest margin, the vote was cast to condemn John Huss to the stake.

For a third and final time, Huss was brought before the assembly on July 6. Though he knew his end was near, his heart was at peace. “I write this letter in prison,” he penned shortly before this final appearance, “and with my fettered hand, expecting my sentence of death tomorrow.... When with the assistance of Jesus Christ, we shall meet again in the delicious peace of the future life, you will learn how merciful God has shown Himself towards me—how effectually He has supported me in the midst of my temptations and trials.”

Standing before the assembly to receive his condemnation, Huss listened to the charges against him.

His answer was the same as ever: He could not give up what he had taught. “I was not forced to come here. I trusted the emperor’s safe conduct,” he added, fixing his eyes on Sigismund, who flushed with shame.

Huss patiently endured the ceremony of mockery and humiliation. When given another opportunity to recant, he replied only that the souls of his people mattered more to him than his poor life. With this, he was sentenced to the stake.

Martyrdom

It seemed as if all of Konstanz came to see Huss take his final stand for truth. Beside townspeople, the richly-dressed clergy and 800 soldiers followed him to the stake. From the council hall, the martyr made his way through the city. He passed his first dwelling place and one last time heard his footsteps echo through the city tower gate.

In a wide, grassy meadow, Huss fell to the ground, praying as his stake was erected. Huss allowed himself to be chained to the stake. Wood and straw were packed around the martyr, and once more he was asked to recant. But Huss had made his decision. Even the flaming branch, about to be laid to the dry tinder, did not terrify him: “All that I have written and preached has been with [the] view of rescuing souls.... therefore, most joyfully will I confirm with my blood that truth which I have written and preached.” The fire was lit.

As the flames licked closer to his face, Huss’s courageous voice could be heard singing, “Jesus, Thou Son of David, have mercy on me.” He sang it twice but never finished the third verse. It was the end. When the charred wood was removed from the stake, Huss’s heart, which had glowed with love for his Savior and his Bohemian people, remained unburned. The fire was then rekindled, and Huss’s ashes were scattered into the Rhine River.

That day was the beginning of a new dawn for Europe. At first, it was just a flickering light, but one that would grow into the greatest blaze the world had ever seen.

Call to Remember

While Huss had only begun to understand Bible truths long concealed by the papacy, he had laid the foundations of a movement. He had taken the first step by challenging the concept that a man must bow to a pope’s decrees before those of the Bible. He had paved the way for those who would follow. “If the goose,” he had written, “which is but a timid bird and cannot fly very high, has been able to burst its bonds, there will come afterwards an eagle, which will soar high into the air and draw to it all the other birds.” Within 100 years, Martin Luther’s Ninety-five Theses would shake all of Europe and begin the mighty Protestant Reformation.

For further study, we suggest the following resource: The Great Controversy.

Download or read The Great Controversy as an eBook for free and/or you can purchase one to read/share with others! You can also listen to The Great Controversy for free.

This article was originally shared at Last Generation Ministries.